By Mollie Lund

Photo Credit: Michael Robinson

In the fall of 2023, Teresa Wiley attended Alamance County’s first Harwood Getting Started Lab. As part of the event, participants were asked to contact three people from their networks to discuss community aspirations using questions from the Harwood ASK Tool, designed to uncover the concerns and aspirations people have for their community.

During this exercise, Teresa had the opportunity to talk with a man who had recently returned to Alamance County after 16 years in prison. During their conversation, he shared his desire for a safe, welcoming community — a sentiment echoed by others in his network of formerly incarcerated men.

Moved by this insight, Teresa collaborated with fellow Harwood public innovators to host Community Conversations with a group of formerly incarcerated men. These interactions shed light on the challenges faced by justice-impacted individuals in Alamance County, especially the unequal access to resources.

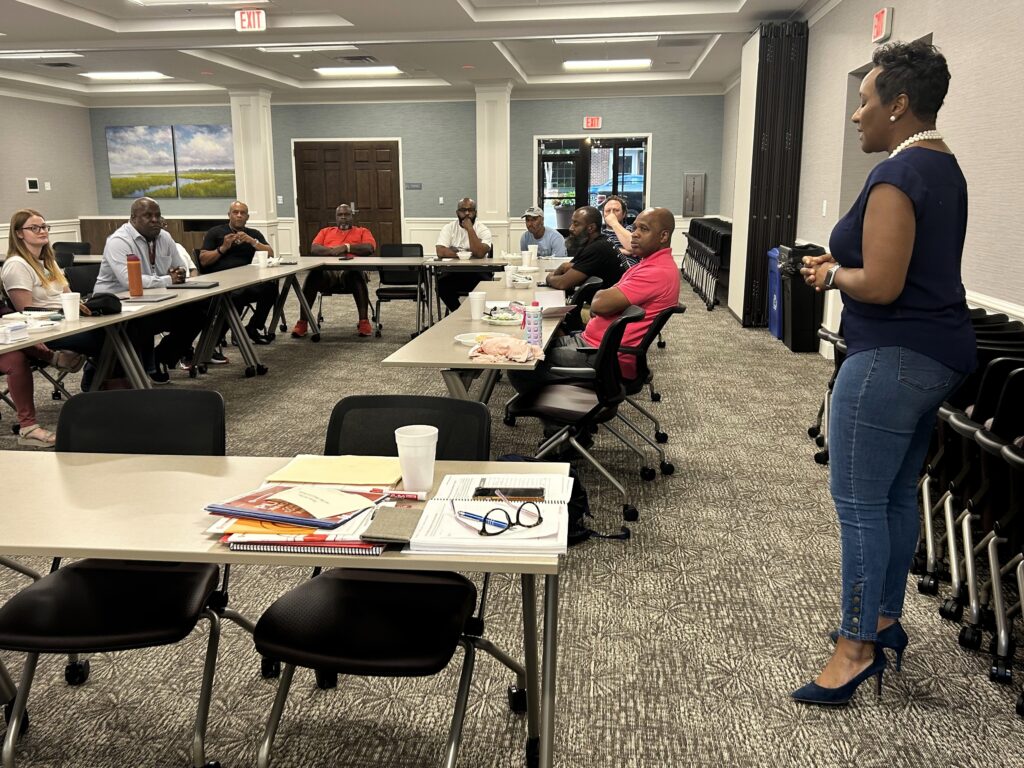

With the help of Michael Robinson, a fellow member of the For Alamance Bridging Team, Teresa established monthly meetings, dubbed “Men In Transition.” These meetings connected formerly incarcerated men with community stakeholders and service providers at the state and local levels, fostering an honest dialogue about the reality of reentry in Alamance county.

“They didn’t know each other,” said Wiley, adding there were organizations willing to support these men but lacked connections to reach them effectively. This led to the exchange of information, contact details, resources, and available training like pamphlets and Peer Support training to bridge the gap.

The meetings have evolved into an informal network that enables Alamance County’s reentry community to connect and support one another, playing a vital role in fostering successful reintegration for formerly incarcerated individuals.

Terrence Vincent, a member of “Men In Transition,” firmly believes in the power of informal networks. He credits much of his reentry success to Michael Kirk, who helped him secure his first job after returning to Alamance County following nearly 15 years in prison.

“When I first came home after doing 14 years, 11 months and nine days, I was lost. I had no one. If I had never met Mike Kirk, I would have never had a job, and I probably would have gone back to the streets,” said Vincent. “It isn’t about what you know but rather about who you know. I wanted to make it a point of emphasis in what we’re trying to build — to make better connections with various people in the community, to make it easier for people when they do come home.”

The monthly meetings enable those impacted by the justice system to connect with resources and opportunities they might not have otherwise known about. Tim Street is a living example of the impact of those connections.

Street learned about a peer support specialist training while talking to Alamance Academy representative Bobby Foster during a monthly meeting between “Men In Transition” members and reentry stakeholders. Alamance Academy is a behavioral health agency that provides mental health, substance abuse and other support to people in the community. After learning from Foster what that role entailed, Street decided to take the course and is now a certified peer support specialist in North Carolina.

The monthly meetings give formerly incarcerated individuals a chance to share their reentry goals, drawing from personal experiences. This empowers them while offering service providers valuable insights into the challenges they face during reentry.

Vincent says there is a need to provide inmates with support services, especially mental health services, to better prepare them for release and reentry.

“If you’re mentally right, and you’re physically right, then you can get yourself acquainted to start going in the right direction — to reenter society and be a great civilian,” said Vincent. “Mental health might be one of the most important things that we need to help people who are entering society. We wouldn’t have a lot of problems, including the crime and recidivism rates that we have if we started helping people early.”

For Street, successful reentry starts in prison and depends greatly on building connections between reentry stakeholders and those in the prison system, including wardens, inmates and especially prison chaplains. “Everybody goes to the chaplain — whether you’re Christian, Muslim or Buddhist, everybody comes and deals with their chaplain,” he said, “so you can really put the chaplain in a position where he’s promoting reentry.”

Wiley believes that bringing together formerly incarcerated men with local and state stakeholders works to create a new path forward for the county’s reentry work. This is especially important with the recent establishment of Alamance County’s state-recognized Reentry Council in the fall of 2024. The designated Reentry Council, located at Sustainable Alamance, is charged with helping formerly incarcerated populations gain and sustain employment upon their release.

“What we know to be true is that when you’re having vulnerable conversations, it’s important to get the community feedback and community engagement,” said Wiley, “I think that one of our areas of opportunity is continuing to work with the newly established Reentry Council to push how important it is to include and hear from the community.”